ENTRAINMENT

Hello lovers of sound and music

It is A really important for who is working with recordings productions and sessions in the music and sound healing field .

Joshua leeds is one of the best in the world as a music and sound producer for healing , treatments disorder ,ect, etc,etc….

all this concepts and so much more plus the practical applications we will learn with his easy and cleaver way to teach in the training at Ibiza Sound healing and therapeutic Music.

More info about the training at Ibiza with Joshua Leeds click this link.

.https://www.facebook.com/events/129944647608327/?acontext=%7B”ref”%3A”3″%2C”ref_newsfeed_story_type”%3A”regular”%2C”feed_story_type”%3A”17″%2C”action_history”%3A”null”%7D

If you are interesting don’t lose this opportunity .

thank you very much for traveling together with the sound and music !

love

Deva

ENTRAINMENT

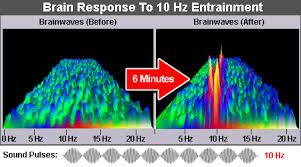

In this book, I have extensively discussed entrainment and the role it plays in psychoacoustics. Entrainment is integral to any musical effect. Not only does it affect our internal landscape through external tempos, but it is also the vehicle by which our body pulses synchronize with each other. Given that rhythm is ubiquitous, entrainment is a vital influence.

So is this valuable tool used in production? I have an awareness of it at all times. For the most part I try to create in the music an easily distinguishable pulse. This makes it easy for the nervous system to latch on and take a ride.

An overarching concept in soundwork is trust. In my productions I do everything I can to win my listeners’ ears. My goal is to help them feel so safe in the arms of my sounds that they will go anywhere the music takes them. I picture an escalator with very comfortable chairs in which listeners gladly recline. With such beautiful sounds and gentle rhythms, they have nothing else to do but to come along for the ride.

An overarching concept in soundwork is trust. In my productions I do everything I can to win my listeners’ ears. My goal is to help them feel so safe in the arms of my sounds that they will go anywhere the music takes them. I picture an escalator with very comfortable chairs in which listeners gladly recline. With such beautiful sounds and gentle rhythms, they have nothing else to do but to come along for the ride.

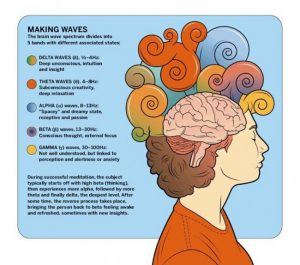

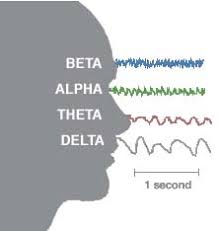

The only time I don’t use easily felt entraining pulses in my production work is when I want no rhythmic movement at all. When I coproduced Andrew Weil’s Sound Body Sound Mind, the purpose was to take the listener to a place most conducive to self-directed healing. The sixty-minute sound track started with a tempo of about 120 beats per minute. Over the first twelve minutes, coproducer Richard Lawrence (1946–2005) and I gradually ramped down to the slowest rubato space we could create. We remained there for thirty-six minutes. Toward the end of this segment, we very gently added a slow tempo, gradually ramping back up to a waltzing pulse of about eighty beats per minute. In the rubato section, called “The Deep,” our job was to create a sonic space that wouldn’t disturb theta and delta brain waves. We had to make sure we did nothing to disturb someone in this space of delicate, subconscious access that had been achieved by our entrainment and the addition of binaural beat frequencies. In this section, rhythm would have been jarring and counterproductive. We made every effort to stay out of any form of pulse. To accomplish this nonentraining effect, we used non-Western instruments—sitar, Bansuri bamboo flute, tamboura, Tibetan bowls—all sounds that could fill the space yet be out of the world of rhythm. Yes, we could have used Western instruments, for any instrument can play rubato (without tempo). But we felt that because we had employed Western instruments in a classical context in the ramping down and then back up, something completely different would contribute to the sense of freedom from form.

The only time I don’t use easily felt entraining pulses in my production work is when I want no rhythmic movement at all. When I coproduced Andrew Weil’s Sound Body Sound Mind, the purpose was to take the listener to a place most conducive to self-directed healing. The sixty-minute sound track started with a tempo of about 120 beats per minute. Over the first twelve minutes, coproducer Richard Lawrence (1946–2005) and I gradually ramped down to the slowest rubato space we could create. We remained there for thirty-six minutes. Toward the end of this segment, we very gently added a slow tempo, gradually ramping back up to a waltzing pulse of about eighty beats per minute. In the rubato section, called “The Deep,” our job was to create a sonic space that wouldn’t disturb theta and delta brain waves. We had to make sure we did nothing to disturb someone in this space of delicate, subconscious access that had been achieved by our entrainment and the addition of binaural beat frequencies. In this section, rhythm would have been jarring and counterproductive. We made every effort to stay out of any form of pulse. To accomplish this nonentraining effect, we used non-Western instruments—sitar, Bansuri bamboo flute, tamboura, Tibetan bowls—all sounds that could fill the space yet be out of the world of rhythm. Yes, we could have used Western instruments, for any instrument can play rubato (without tempo). But we felt that because we had employed Western instruments in a classical context in the ramping down and then back up, something completely different would contribute to the sense of freedom from form.

One of the vehicles I employed when working with the Arcangelos Chamber Ensemble is pizzicato—lightly plucking strings, rather than using the bow. This provides a gentle rhythmic pulse. Quite often Lawrence and I would take an existing internal voicing and have the string players pluck each note instead of using the normal legato bowing. The effect, especially with multiple players, is a wonderful round sound that provides an easily recognized rhythmic pulse. Track 8 in the embedded audio is our arrangement of Vivaldi’s Largo from the Oboe Concerto in Ba Major. When listening to this arrangement, notice the use of the pizzicato. It creates an ongoing, nonobtrusive effect. Yet psychoacoustically, this gentle plucking becomes an escalator. Your nervous system locks on to this external periodic pulse and will match it. Volumes can become quite low, yet the nervous system is attuned to the rhythm.

Often, in the course of a piece, we will either gradually speed up or slow down, depending on where we want to take the listener. Effective use of entrainment involves the periodicity of the tempo. Therefore, the goal is to stay as regular in pulse as we can. If we become too erratic, the entrainment will not be successful. Notice how on track 6, our rendition of Mahler’s Poco Adagio from Symphony no. 4, the pulse is set by the pizzicato bass, then gradually slows, then slows even more. Using the iso principle, our goal was to sonically meet listeners near the tempo we imagined their body pulses would be when first lying down. The intention of the album is to facilitate falling asleep. Therefore, our destination, simply put, was to transport the listener into as slow a zone as we could. By the end of the piece, notice how we reach almost a nontempo state. In the process, the bass pizzicato comes in and out. But because we established this as the pulse initially, we assume that each time it returns it is recognized as the rhythmic escort. With entrainment, that is essentially what we are doing. We are merely a body pulse escort service!

the power of Sound

Joshua Leeds.